Nos Galan Gaeaf Hapus

During Roman Britain, people celebrated a festival very like Samhain it was called Galan Gaeaf.

When the Romans invaded England, they began to see its celebrations blend with their own traditions:

Feralia a Roman festival to honour the dead, sharing the same reverence for ancestors.

Pomona a Roman celebration for the goddess of fruit and trees. which gave rise to the tradition of bobbing for apples.

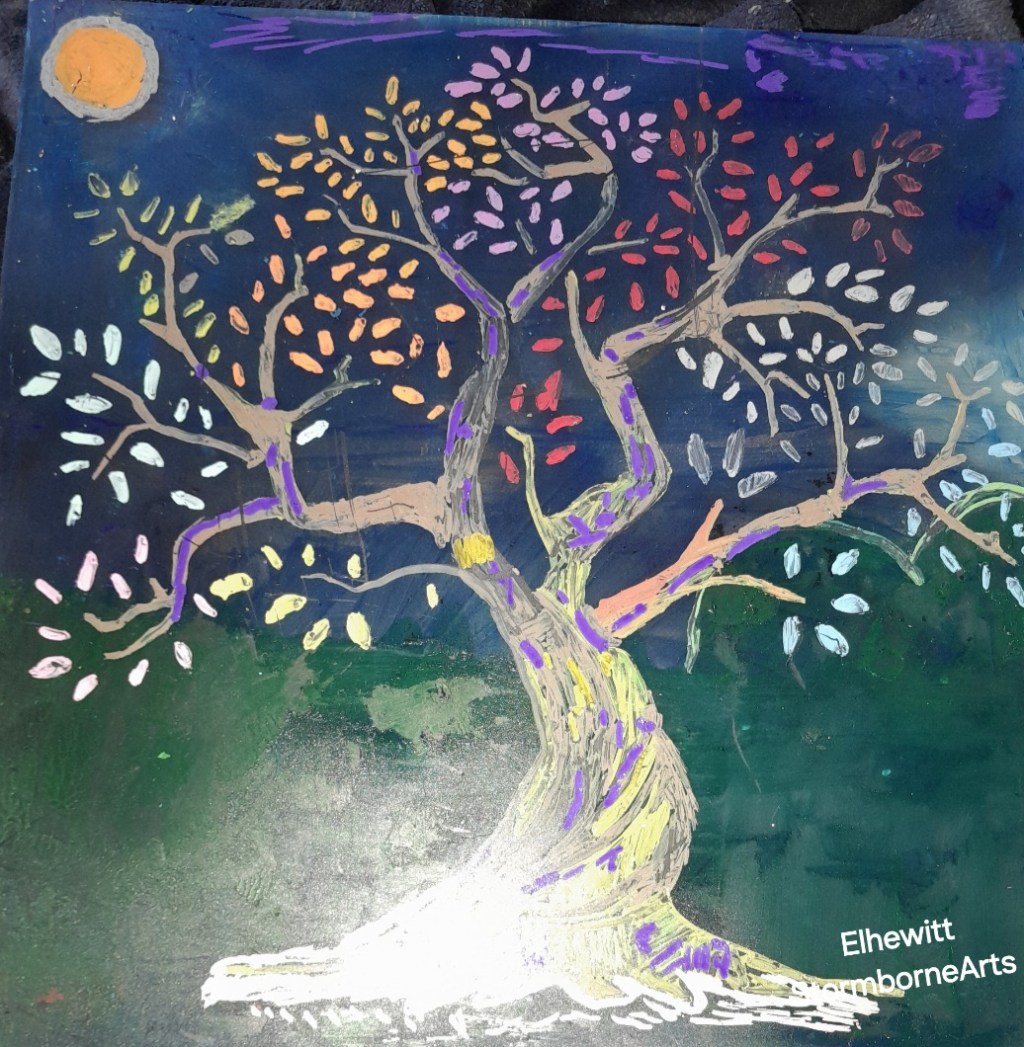

Galan Gaeaf is an Ysbrydnos a spirit night. when the veil between worlds thins and spirits walk the earth.

The term first appears in literature as Kalan Gayaf. In the laws of Hywel Dda, and is related to Kalan Gwav.

In Christian tradition, it became All Saints’ Day, but for those who still celebrate Calan Gaeaf. It remains the first day of winter a time of endings, beginnings, and remembrance.

Let us not forget our past our warriors, our farmers, and the land itself that gives us life.

Ancient Traditions

As a harvest festival, farmers would leave a patch of uncut straw. Then race to see who can cut it fastest. The stalks were twisted into a mare, the Caseg Fedi.

One man would try to sneak it out in his clothes. If successful, he was rewarded; if caught, he was mocked.

Another tradition, Coelcerth, saw a great fire built. Each person placed a stone marked with their name into the flames. If any name-stone was missing by morning, it was said that person would die within the year.

Imagine the chill of dawn as people searched the ashes for their stones!

Then there was the terror of Y Hwch Ddu Gwta. The black sow without a tail and her companion, a headless woman who roamed the countryside. The only safe place on Galan Gaeaf night was by a roaring hearth indoors.

Superstitions were everywhere:

Touching or smelling ground ivy was said to make you see witches in your dreams.

Boys would cut ten ivy leaves, discard one, and sleep with the rest beneath their pillows to glimpse the future.

Girls grew a rose around a hoop, slipped through it three times. cut the bloom, and placed it under their pillow to dream of their future husband.

It was also said that if a woman darkened her room on Hallowe’en night and looked into a mirror. Her future husband’s face would behind her.

But if she saw a skull, it meant she would die before the year’s end.

In Staffordshire, a local variation involved lighting a bonfire and throwing in white stones . If the stones burned away, it was said to foretell death within a year.

Food and Feasting

Food is central to the celebration. While I don’t make the traditional Stwmp Naw Rhyw. a dish of nine vegetables I make my own variation using mixed vegetables and meat.

There’s little real difference between the Irish Gaelic Samhain and the Welsh Calan Gaeaf.

Each marks the turn of the year the death of one cycle and the birth of another.

Over time, every culture left its mark: the Anglo-Saxons with Blōdmonath (“blood month”). Later Christian festivals layered upon the old ones.

The Borderlands of Cheslyn Hay

I was born in a small village called Cheslyn Hay, in South Staffordshire. WHhich I think is about five miles from what the Norse called the Danelaw, the frontier lands.

Before the Romans came, much of Staffordshire and indeed much of England was part of ancient Welsh territory.

Though little is known of this period, imagination helps fill the gaps between the facts.

The Danelaw was established after the Treaty of Wedmore (878 CE). Between King Alfred of Wessex and the Viking leader Guthrum.

It divided England roughly from London northwards, trailing the Thames, through Bedfordshire, along Watling Street (A5), and up toward Chester.

Watling Street the old Roman road that passes through Wall (near Lichfield). Gailey was often described as the de facto border between Mercia (to the west) and the Danelaw (to the east).

Cheslyn Hay lies just west of Watling Street, near Cannock and Walsall. Placing it right on the edge of Mercian territory within sight of Danelaw lands.

Because of that proximity, the area would have been influenced by both sides.

Norse trade routes and settlers passed nearby, along Watling Street and the River Trent.

Villages like Wyrley, Penkridge, and Landywood show both Old English and Celtic/Norse roots.

It’s easy to imagine that my ancestors have traded or farmed alongside Norse settlers. after all, many Vikings were farmers too.

Part of my family came from Compton and Tettenhall Wood. Where a local battle is still spoken of today; the other side from Walsall.

Archaeological finds near Stafford and Lichfield suggest Viking artefacts and burial mounds, linking the landscape to that history.

So while Cheslyn Hay wasn’t technically within the Danelaw. It stood upon the Mercian frontier what I like to call “the Border of the Ring” . where Saxon, Norse, and Brythonic traditions once met and mingled.

My Celebration Tonight

As I live in a flat, I’ll light a single candle instead of a bonfire. Cook a small feast vegetables and pork with a potato topping.

For pudding, I’ll have blueberries, strawberries, and banana with an oat topping and warm custard.

I’ll raise a glass to my ancestors and set a place at the table for any who wish to join.

Thank you for reading.

Nos Galan Gaeaf Hapus